These overarching resources provide foundation knowledge about social work with people with dementia.

“Dementia is not an inevitable part of ageing and is not a disease in its own right. It is an umbrella term. It describes the symptoms that occur when the brain is affected by certain diseases or conditions which cause the gradual death of brain cells. This leads to progressive cognitive decline.” (SCIE Guide, About dementia. Available at: http://www.scie.org.uk/dementia/about/)

Symptoms can include changes to memory, thinking, decision-making, perception, problem-solving, understanding and language. In the end stages people can lose the ability to control movement, including sitting up, smiling and swallowing. Dementia is different to the normal memory loss associated with getting older. Although memory often deteriorates with age, dementia is characterised by multiple cognitive deficits that impact on daily living.

Recent Alzheimer’s Society research shows that 850,000 people in the UK have been diagnosed with a form of dementia. By 2025, this will hit a figure of 1 million. These are figures for those with a diagnosis and it does not include other adults who, for various reasons, are undiagnosed.

Types of dementia

There are many different types of dementia, the most common of which are:

- Alzheimer’s disease (62 per cent of cases): Characterised by the development of ‘plaques’ (abnormal clusters of protein fragments) and ‘tangles’ (collapsed Tau proteins) in the structure of the brain, resulting in the death of neurons.

- Vascular dementia (17 per cent of cases): Often caused by a stroke or a series of mini strokes, causing problems in the supply of blood to the brain.

- Mixed dementia (10 per cent of cases): A dual diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

- Dementia with Lewy bodies (4 per cent of cases): Caused by protein deposits called Lewy bodies in the brain, leading to similar symptoms to Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Fronto-temporal: Lobe degeneration – can affect personality and behaviour.

- Korsakoff’s Syndrome: Commonly caused by long term alcohol misuse.

- HIV-related: Sometimes as a result of late diagnosis & non treatment.

- Parkinson’s Disease.

There are over 100 different types of dementia. You need to understand the different types, but also the different impacts they have and the way they progressively impact on the person.

You can read fact sheets from the Alzheimer’s Society about the different types of dementia at: www.alzheimers.org.uk/factsheets.

The Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Brain Tour provides a helpful set of video clips to help you.

More information about symptoms can be found here: www.scie.org.uk/dementia/symptoms/.

Many people diagnosed with dementia will be living with at least one other long-term health condition. Some people will be coping with ‘dual diagnosis’, when they have dementia in addition to another known disability. For example, an adult in later life with dementia and autism will have specific needs that will need to be assessed and understood (Department of Health (2015) A manual for good social work practice: Supporting adults who have autism).

Social workers should be aware of conditions that can sometimes be mistaken for signs of dementia, for example a urinary tract infection (UTI) which is common in older adults, depression or brain injuries. As a consequence of a singular episode of poor health, people can often be labelled as having dementia without any evidence, tests or formal diagnosis.

Dementia is considered ‘early onset’ when it affects people under 65 years of age. It is also referred to as ‘young onset’ or ‘working age’ dementia. However this is an arbitrary age distinction which is becoming less relevant as increasingly services are realigned to focus on the person and the impact of the condition, not the age. More information can be found here: www.youngdementiauk.org/about-young-onset-dementia-0.

Law and policy

The Care Act 2014 requires “Local authorities [to] promote wellbeing when carrying out any of their care and support functions in respect of a person.” (1.2) The act also contains duties to provide information and advice, prevent needs for care and support, and promote integration of services.

The person’s right to take part in discussion and planning is enshrined in the Care Act. The act has introduced a duty to ensure that where an adult may be unable to fully participate in any assessment or review of their needs, they are offered access to an advocate.

Needs assessment under the act includes looking at needs, the impact of needs, the outcomes someone wants to achieve, and what would support them, including their own strengths and capabilities, and their wider support network or community. A carer’s assessment must be considered when assessing the cared-for person’s needs.

Social workers need to be confident in the principles contained within the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Equality Act 2010, as well as the principles and practice of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (see Department of Health curriculum guide on the Mental Capacity Act 2005). Safeguarding should be done with, not to, people and should be focused on personal outcomes that someone has, in line with Care Act guidance on making safeguarding personal.

In 2009, the Government published its first National Dementia Strategy (Department of Health, 2010), in order to enable people to ‘live well with dementia’. This set standards for dementia care that included increased and timely diagnosis, the need for increased early intervention services and the need for the development of flexible and reliable community support services based on the identified personal needs and preferences of people with dementia and their carers. An outcomes framework written from the perspective of a person with dementia was also published to support implementation of the National Dementia Strategy. The Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge encouraged a shift away from seeing dementia as just a health and social care issue to something that affects entire communities.

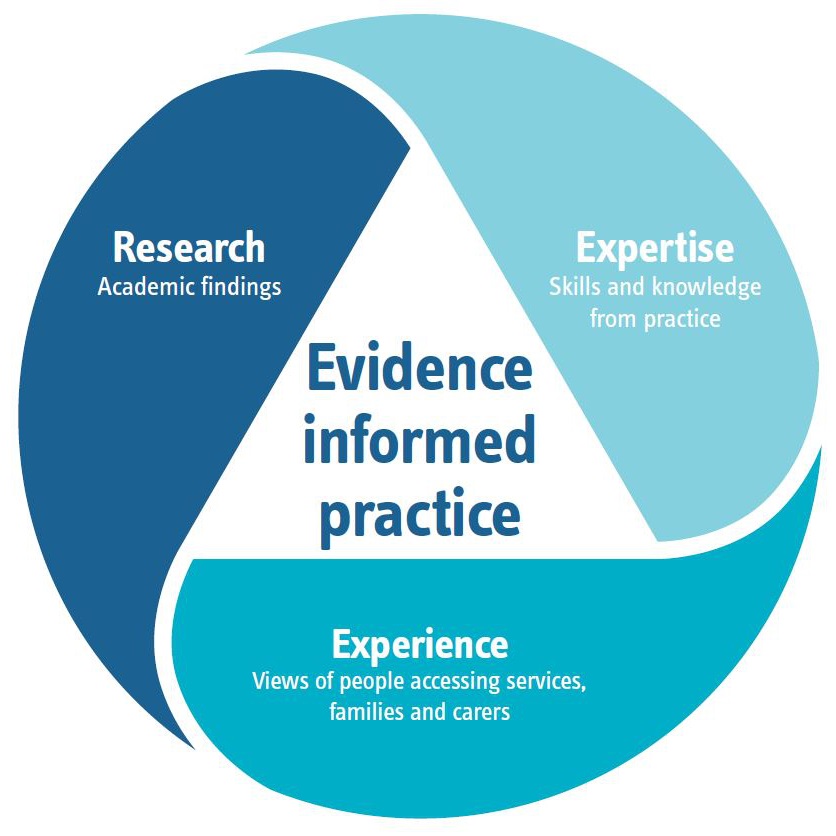

Evidence-informed practice

‘Evidence-informed practice’ (EIP) refers to a particular methodology used in the design, delivery and evaluation of social care services.

An evidence-informed approach draws on information from research and academic studies, bringing it together with the expertise and wisdom from practice and the views and experiences of people accessing services.

It considers the evidence from these three sources alongside each other and gives a rich insight into key issues to inform decision-making and enable effective practice.

This gives leaders, managers and practitioners the confidence to make decisions that are grounded in the evidence of what is known to work.

EIP is distinct and different to ‘evidence-based’ approaches, which only reference evidence from academic research.

‘Whilst single sources of information in isolation can be misleading, scaffolding knowledge by bringing together different sources of information can help distinguish myths, ideologies and preferences from things that have some basis in evidence.’

Dez Holmes,

Director, Research in Practice and Research in Practice for Adults

Project methodology

The methodology used to develop the dementia resources aims to:

- ensure transparency about the approach taken

- further explain the methods used

- identify learning from this approach to inform other work.

Values

The values that we work to are:

- Involvement – of people with lived experience through co-production.

- Authenticity – of the resources so that they reflect real experience.

- Evidence-informed – resources that draw on the views of people living with dementia, practice experience and research.

- Helpfulness – of resources that are accessible, relevant and practical.

Approach

The Department of Health specified that there should be three case studies based around three different situations which would illustrate how resources might be used to inform practice.

A Research in Practice for Adults (RiPfA) project team of four staff and associates led by a project manager was established, who had expertise in: social work practice; training transfer; social work practice education; scoping evidence; product development; and information technology.

The case studies drew from real experiences described by people living with dementia in research narratives and from practitioners’ experience, including that of caring for own family members with dementia.

The Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) network of dementia support groups were approached to ask for comment on the authenticity of case study material. Case studies were also sent to practitioner reviewers to send on to dementia support groups they have contact with.

The tools and website development materials were sent out for review by practitioners via the principle social worker network.

Co-production challenges

Response from the dementia networks was understandably limited – the reason given being that the pressures on families of people with dementia make it impossible to read and comment. The feedback which was received confirmed the authenticity of the case studies.

Feedback from practitioner networks on each case study underpins the ‘Social care assessor conclusion’ and ‘Eligibility decision’ of each assessment.

Timeline: Steps of the project

Jan-Feb 2017

- design the website map

- locate resources from the manual into relevant sections of the site map

- conduct a wider evidence review

- develop case studies and accompanying tools.

Feb-March 2017

- develop and build the site

- first draft of site completed by end March.

March-April 2017

- test and evaluate site.

April-May 2017

- revise from feedback given.

May 2017

- launch site during National Dementia Awareness Week (15-21 May)

whathealth.com/awareness/event/dementiaawarenessweek.html - deliver launch webinar – 18thMay 2017.

Practice and research evidence

A review of the evidence was undertaken to support the development of resources by:

- Looking at evidence from the last five years available on the web including academic literature, recent government policy and examples of good practice.

- Identifying research underpinning a growing understanding of different types and stages of dementia and people’s experiences of living with these conditions.

- Identifying themes and messages related to social work effectiveness, or effective work from other professions, which is transferrable.

From this review it was decided to structure the material from the Department of Health’s original manual and evidence review around five key areas of practice in social work with people with dementia: starting with the person, maintaining the relationship, involving others, upholding people’s rights and working with change.

This approach reflects RiPfA’s commitment to evidence-informed practice which draws upon on lived experience, practitioner experience and research evidence to identify implications and messages for practice.

Topics and tools

We used the practice evidence review to identify key messages for each theme and searched for supporting material on dementia available on social care websites including: Research in Practice for Adults; Social Care Institute of Excellence; Care Act guidance; NICE; British Association of Social Work (and former College of Social Work resources); Department of Health; Skills for Care; and dementia specific websites such as Alzheimer’s Society and Young Dementia UK. For each theme we identified useful documents to signpost to and located or created practice tools.

Webinar

During launch week, Research in Practice for Adults delivered a webinar to introduce the website and resources, which was attended by 115 practitioners. The webinar drew on training transfer evidence including the voices of people living with dementia and their carers, and an opportunity to explore how the site might be used in practice. The webinar was recorded and is available here.

Useful links

- Dementia evidence toolkit: toolkit.modem-dementia.org.uk/

- Dementia resources SCIE: www.scie.org.uk/dementia/

- Dementia standards NICE: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs1

- Dementia core skills education and training framework: cdn.basw.co.uk/upload/basw_33423-4.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Society: www.alzheimers.org.uk/

- Young Dementia UK: www.youngdementiauk.org/about-young-onset-dementia-0

- Dementia friendly communities Joseph Rowntree Foundation: www.jrf.org.uk/people/dementia

- Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia implementation plan 2016: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507981/PM_Dementia-main_acc.pdf

- Housing and dementia: www.housinglin.org.uk/Topics/browse/HousingandDementia/

- Social Work Practice with Older People: gsw.ripfa.org.uk/